Carbon markets channel climate finance toward measurable environmental outcomes through three distinct types of carbon credits: carbon avoidance credits, carbon reduction credits, and carbon removal credits.

The baseline scenario serves as the key differentiator between these carbon credit types.

Current voluntary market composition reflects cost and availability dynamics. According to Climate Focus VCM Dashboard data, total issuance reached 287 MtCO₂e in 2024. This issuance includes nature-based removal projects showing remarkable stability throughout the year.

Carbon avoidance credits are the largest share of voluntary carbon markets. They certify that projects have prevented emissions that would have happened if nothing had changed.

The key idea behind these credits is the counterfactual baseline. Developers use statistical modeling to show what would have happened without the carbon finance intervention. For example, REDD+ projects (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) focus on forest conservation and estimate avoided deforestation by comparing observed outcomes against projected deforestation trends based on historical data.

These credits can also come from renewable energy projects that show clean electricity is replacing fossil fuels on regional grids.

Statistical modeling can be uncertain because it is based on predictions about the future. These predictions, in turn, depend on things like economic growth and policy changes that are hard to verify. Another challenge is leakage, where emissions just move elsewhere instead of being reduced.

Despite these challenges, avoidance credits can deliver significant co-benefits, including biodiversity protection, improved community health, and support for Indigenous rights. As a result, avoidance credits continue to play an important role in corporate climate strategies, particularly for companies seeking alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Carbon reduction credits certify measurable decreases in emissions from ongoing operations against documented historical baseline performance.

Rather than modeling counterfactual scenarios, reduction projects compare current emissions against documented past performance. This observable reference point provides stronger verification confidence than statistical projections.

Verification complexity varies significantly by project type. Fuel-switching initiatives offer straightforward tracking through utility meters using standardized emission factors from databases such as the EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) and methodologies developed under the UNFCCC Clean Development Mechanism (CDM).

Methane capture projects require technically specific monitoring and advanced gas analysis systems, enabling relatively direct and robust verification. In contrast, cookstove distribution programs involve a different type of complexity, as they rely on sophisticated MRV systems to capture household adoption, usage patterns, and emissions across diverse fuels and stove technologies at scale.

Clean cooking initiatives illustrate sophisticated MRV requirements for behavioral program credibility.

The iRise project in Malawi exemplifies robust MRV approaches aligned with Gold Standard methodology requirements, utilizing iVerify software with NFC (Near Field Communication) technology to monitor cookstove usage across distributed households.

This enables real-time tracking and transparent verification of carbon credit generation. Optimistic baseline assumptions about traditional stove fuel consumption can cause over-crediting if actual adoption rates prove lower than projected.

Reduction credits enjoy strong compliance market acceptance including CORSIA and EU ETS because historical baselines offer verifiable documentation that auditors can examine with confidence.

Carbon removal credits — also termed CDR credits — represent a small but growing segment of voluntary markets, attracting disproportionate institutional attention. These instruments certify that CO₂ has been actively extracted from the atmosphere and durably stored.

Reforestation and afforestation projects capture carbon from the air through photosynthesis, locking it away in trees and soil. Meanwhile, peatland restoration helps stop carbon emissions from damaged wetlands while also restoring the carbon stored in those ecosystems.

Nature-based approaches currently dominate the carbon removal market, driven by their cost-effectiveness, scalability, and the availability of well-established methodologies. These solutions play a critical role in delivering near-term removal capacity while generating significant co-benefits for biodiversity, ecosystems, and local communities.

At the same time, as highlighted in assessments by the IPCC Working Group III, durability remains an important consideration for biological carbon storage. Nature-based carbon stocks can be exposed to reversal risks from wildfires, disease outbreaks, pest infestations, and future land-use changes.

Rather than undermining their value, these risks underscore the importance of robust project design, long-term management, and institutional safeguards to ensure the integrity of nature-based carbon removal.

Direct Air Capture (DAC) technologies use chemical processes to extract CO₂ directly from ambient air for permanent geological sequestration. According to the IEA, DAC plants have been successfully operated in various climatic conditions, with major projects announced in the United States, Europe, and the Middle East.

Biochar production pyrolyzes organic waste into stable carbon structures resisting decomposition for centuries while improving soil fertility. BECCS (Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage) combines biomass energy generation with carbon capture.

Engineered approaches offer significantly higher permanence. Major purchasers including Microsoft, Stripe, and the Frontier Fund have committed significant advance purchases to support commercial deployment

Carbon credit quality depends on five universal criteria that determine integrity across all credit types.

Major certification standards including Verra VCS and Gold Standard require all five criteria as universal integrity benchmarks. In 2024, the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM) initiated assessments and designated several carbon-crediting programs as CCP-Eligible and multiple methodologies as meeting the Core Carbon Principles, advancing the establishment of a global quality benchmark for voluntary carbon credits.

Voluntary carbon markets operate without regulatory mandate — corporate buyers pursue credits for CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) commitments, net-zero pledges, and stakeholder expectations.

Compliance markets operate under regulatory frameworks with mandatory requirements. Under CORSIA, airlines in participating States are required to offset the growth in their CO₂ emissions by using eligible Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF), CORSIA Eligible Units (CEUs) issued by ICAO Technical Advisory Body-approved crediting programs, or a combination of both. The EU ETS sets cap-and-trade parameters for industrial emitters.

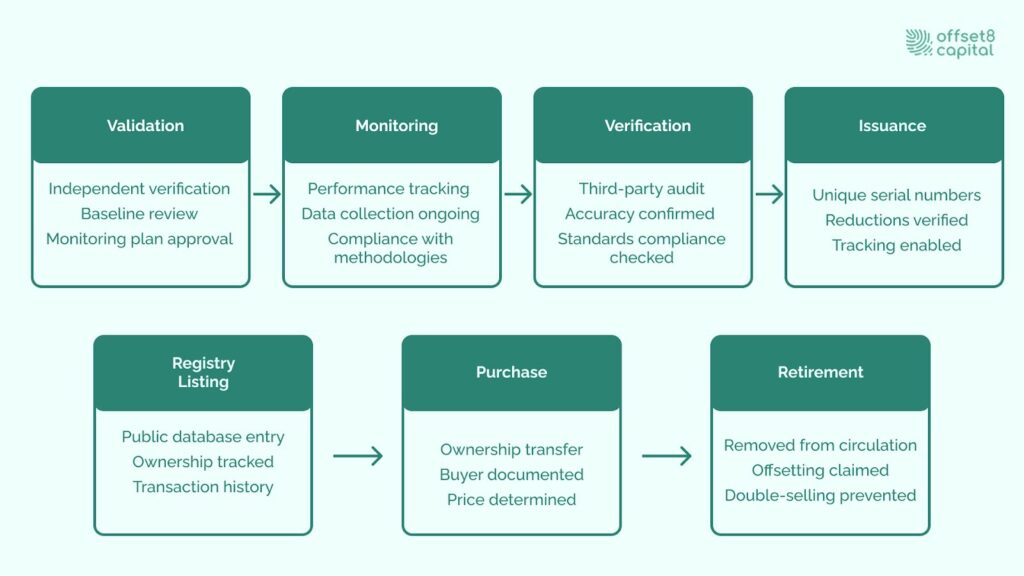

Fig 1: Carbon Credit Lifecycle

Carbon credits follow a multi-stage lifecycle designed to ensure transparency and prevent fraud.

Validation: Independent verification bodies assess project documentation. The documentation includes baseline calculations, additionality demonstrations, and monitoring plans against relevant standard requirements.

Monitoring: Project performance tracking to ensure that emission reductions or removals are happening as planned. It includes data collection, reporting, and compliance with predefined monitoring methodologies.

Verification: Verification involves independent third-party bodies confirming the accuracy and authenticity of the reported emission reductions or removals. The process ensures that the project meets its claimed objectives and complies with relevant standards.

Issuance: Credits receive unique serial numbers after verification of actual emission reductions or removals. It enables tracking throughout subsequent transactions.

Registry Listing: Public databases operated by standards bodies like Verra and Gold Standard track ownership, transaction history, and status for each serial number.

Purchase: Ownership transfers from project developers to corporate or government buyers with recorded documentation.

Retirement: Credits permanently removed from circulation when used for offsetting claims, preventing double-selling. Registries maintain permanent retirement records enabling public verification of corporate offset claims.

The year emission reduction occurred is called vintage. Vintage affects pricing and compliance eligibility. Some frameworks restrict eligible vintages to ensure credits represent recent climate action.

Regulatory frameworks increasingly shape carbon credit demand and quality requirements.

CORSIA (Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation) represents the first global market-based measure applying to an entire sector. Administered by ICAO, CORSIA requires airlines to offset CO₂ emissions growth above established baselines.

Key parameters:

The 2024 Sector's Growth Factor was calculated at 0.154, based on total 2024 emissions of 361 million tonnes against the baseline of 305.5 million tonnes. Airlines calculate offsetting requirements by multiplying emissions by this annual factor, reducible through CORSIA Eligible Fuels before purchasing remaining obligations.

Article 6.2 of the Paris Agreement establishes the framework for international carbon trading, enabling bilateral cooperation between countries on emission reductions. Host countries can transfer mitigation outcomes to buyer countries in exchange for investment, technology access, and capacity building support.

Transferred units are termed Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOs). The accounting mechanism requires corresponding adjustments. When a country exports mitigation outcomes, it adds equivalent emissions to its national inventory. The purchasing country subtracts equivalent emissions.

Japan's Joint Crediting Mechanism (JCM) exemplifies bilateral frameworks operating under Article 6.2 principles, enabling project-based transfers between Japan and partner countries with proper corresponding adjustments.

As organizations pursue carbon neutrality or net-zero emissions, the quality of carbon credits is a critical determinant of effective climate strategies. The way credits are chosen directly impacts the success of a net-zero emissions strategy. Rather than competing, the three types of credits (avoidance credits, removal credits, and others) work together to achieve long-term goals.

The emission reduction hierarchy prioritizes cutting emissions at the source through efficiency and renewable energy adoption.

High-quality offsets that meet strict verification standards are crucial for addressing emissions that can't be reduced directly. Avoidance credits are cost-effective and bring additional co-benefits that operational changes can’t match.

The key to quality lies in integrity, not just the type of credit. When choosing credits, focus on additionality, solid MRV systems, and clear registry documentation.

Organizations are increasingly sourcing credits through regulated channels that ensure due diligence and direct relationships with project developers.

The three types of carbon credits — avoidance, reduction, and removal — serve distinct strategic purposes within comprehensive climate approaches. Quality criteria including additionality, permanence, leakage accounting, MRV robustness and double-counting prevention transcend credit categories as universal integrity determinants.

Regulatory evolution through CORSIA, Article 6.2, and government-led bilateral mechanisms such as Japan's JCM is raising global standards for carbon credit integrity. Effective climate strategies combine direct emission reductions with carefully selected, high-quality offsets sourced from credible projects supported by transparent verification and close engagement with project developers. Organizations should assess climate goals, stakeholder expectations, compliance requirements, and budget constraints to build portfolios balancing cost-effectiveness, permanence, co-benefits, and regulatory alignment.

Disclaimer

This commentary is for informational purposes only and should not be considered financial, investment, or regulatory advice. Offset8 Capital Limited is regulated by the ADGM FSRA (FSP No. 220178). No assurances or guarantees are made regarding its accuracy or completeness. Views expressed are our own and subject to change

Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) captures CO₂ at emission sources — power plants, cement facilities, steel mills — before atmospheric release, preventing new emissions. Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) extracts existing atmospheric CO₂ through Direct Air Capture or nature-based approaches like reforestation, reversing past emissions. BECCS combines both: biomass absorbs atmospheric CO₂ during growth, then combustion emissions are captured and stored.

A CDR credit certifies one tonne of CO₂ actively removed from the atmosphere and durably stored through engineered methods (DAC, biochar, BECCS) or nature-based approaches (reforestation, peatland restoration, soil carbon management). CDR credits address existing atmospheric carbon accumulated from historical emissions.

"Carbon offset" serves as an umbrella term encompassing all credit types — avoidance, reduction, and removal. "Carbon removal" specifically refers to atmospheric CO₂ extraction projects. All carbon removal credits qualify as offsets; not all offsets involve removal.

Yes. Agricultural producers can generate credits through soil carbon management, biochar application, agroforestry, and methane in flooded rice systems using Alternate Wetting and Drying (AWD), and livestock methane reduction. Projects must demonstrate additionality — practice changes from conventional baselines — and implement MRV systems verifying carbon stock increases.

Critics cite high costs, concerns that CCS enables continued fossil fuel dependency rather than forcing renewable energy transition, and geological storage leakage risks — though studies indicate under 0.1% per century in suitable formations. Proponents argue CCS remains necessary for hard-to-abate sectors including cement, steel, and aviation where technological alternatives remain limited.